The first session

of our mini-series set the stage on some of the issues we are seeing regarding

soil health and long-term resiliency in protected spaces. For those of you who missed the first session, or are

interested in revisiting the teachings before building on it in part 2, you can

find the full recording here (Managing Nitrogen in Protected,

Soil-Based Systems). A summary of some of the

information presented is listed below:

One of the

re-occurring themes in protected soil production is an accumulation of

nutrients, specifically things like Mg, Ca, and K, as a result of large

deposits of compost before a cropping season. While these are necessary

nutrients for healthy crop production and good quality fruit, too much of a

good thing is not always a good thing. Typical supplementation focuses so

heavily on achieving a target N value, that a lot of the micronutrients that

come along with that N slip by unnoticed.

Not only are we

concerned with high levels of certain micronutrients, but also have to be aware

of the soil structure itself. One of the soil health indicators we talk a lot

about is percent organic matter. While we like

to see higher percentages of organic matter, it can come at a cost to other

macro- and micro- nutrient availability to the plant when not executed

properly. Paying attention to the cation exchange capacity value, or CEC, on a

soil test, is important for those who regularly apply compost. While not

mentioned in this webinar with Judson, the higher the CEC value, the tighter

bond exists between the soil particles and the nutrients, which make it harder

to make adjustments to the nutrient composition/balance without significant

intervention.

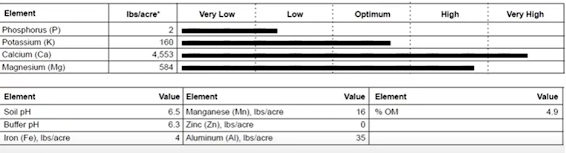

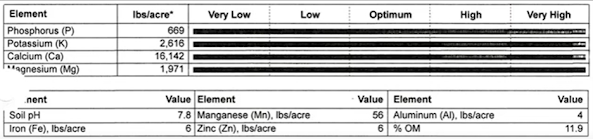

Combine these two factors with the lack of overhead precipitation in tunnels, we see astronomical values of these micronutrients, which are going to contribute to a rising pH, and a significant hinderance on the plant's ability to take up all of the nutrients in the required quantities/balances that the crop needs. Here is an example of the soil test presented in the webinar highlighting this exact trend. The top image highlights a soil that has been supplemented but not to any excessive extent, and the second image highlights how that soil has evolved with continual additions of a compost:

When

it comes to the use of compost in protected settings, conducting a compost

analysis before application is strongly encouraged, as is yearly soil testing

so that we see what is happening in these soils that do not have the same

opportunities for drainage as an exposed soil would. Understanding exactly what

you are putting into the soil, and how often, is crucial to avoiding buildup to

the levels displayed here. Generally when it comes to supplying nutrients to

the crop, scenarios that require supplementation are much easier to navigate

compared to a heavily loaded and complex soil as what is projected above. The

use of fertilizer blends can also contribute to the accumulation of certain

nutrients. Consider this - the go-to fertilizer you use in your system is

20-20-20. While that is a great source of nitrogen, your P and K are already

very high, and is going to add to the already-existing nutrient load. In soils

such as these, single nutrient sources are going to be a much better choice as

we attempt to remediate these soils into something that are resilient and will

support crop production well into the future.

Given all of this

information, what can we do to better balance out our nutrient supplementation

to prevent this from happening? One of the best strategies is going to be split

nutrient, application throughout the season. This is a much more targeted

approach, where we know:

1)

nutritional targets for the crop in question

2)

recent soil tests outlining nutrient composition

3)

BONUS when we consider the long-term nutrient output of supplements such

as

compost or manure

From here, we are able to formulate a plan that sees

regularly scheduled nutrient introduction via fertigation into the tunnels,

specifically targeted for when the plant needs those nutrients the most. In

doing so, we can reduce the loss of nitrogen to the environment, prevent

unnecessary buildup that impede production success, maximize the impact that

each $$ of fertilizer has on crop performance, and generally contributes to

resilient and long-lasting productivity of those greenhouse soils.